Braids, Eggs, & Legs: a Wandering

October/November 2023

Catskill Art Space, Livingston Manor, NY

A sense of serious satire has pervaded Nancy Davidson’s work for many years. A current grouping of her work can be found at Catskill Art Space generously installed across two large gallery spaces for a show Davidson titles, “Braids, Eggs, & Legs: A Wandering”.

A long-term fan of morselized language and bodies sundered into their various parts, Davidson’s work should be a field day for a psychoanalytic read. And yet, here, she cautiously elides both the psychosexual menace and violence that, say, the filter of Melanie Klein could offer and, to the work, despite the punning titles, foreswears the endless looping semiotics of a Lacanian read. Instead, Davidson is to be found, or lost, wandering, as her title indeed announces.

One version of this wandering might begin with Eden. You know, the apple, the snake, the eviction; eternal wandering until the return is okayed. Davidson picks up this narrative somewhere after that initial exile with a nod to Joyce’s Ulysses and thus to the Homeric circular journey that returns to where it all began, aka Eden. It was during the Covid Lockdown, when a person was pretty much prohibited from wandering that Davidson embraced Joyce’s novel. While the whole cycle of Leopold Bloom’s meanderings around Dublin were the backstory for Davidson’s thinking as she prepared for this show, the image most precisely lifted from the text, and almost hidden in plain sight in the current show is the “ashphant”: Joyce’s neologism for a walking stick crafted from a stout shaft of Ash. Folding the intertextual references one upon the other, Davidson re-dubs Joyce’s already pun laden object the “Hecatesstick”.

Hiding in plain sight bears some elaboration. The “Hecatestick” is merged into the installation titled Source or Omphalos (2023). Source being an installation claiming territory across fully one half of one of the galleries. It is a piece that evokes thresholds or entryways, perhaps even a proscenium arch. And while Source, like much of Davidson’s work, deploys a lurid palette that can seem to run against nature, Hecatestick hails the viewer’s attention ever more so against nature. This rendering of a wooden walking stick has a kryptonite glow to it! A walking stick sourced on Etsy, Davidson has cast it in translucent mint green resin; it gets one’s attention!

Having traveled with Joyce to the classical world Davidson puts mythology to work. In Greek antiquity Hecate was a God associated with sorcery and necromancy but also –and this is perhaps the more important piece for Davidson– with thresholds, places in-between places, times between times: transitions from one thing to another. Hecate was associated with the twilight, with a space and time that evokes imprecision. This, I think, is the true territory of Davidson’s intellectual and aesthetic wanderings. To disassemble what we think we know.

In so much of her work, by deploying a parodic version of the expected, Davidson dismantles that expectation, the known becomes its reverse. Davidson knows the subversive power of parody or a pun. She knows how to wield exaggeration, excess and amplification. With this practiced set of strategies, she accosts questions of sexuality, and power brandishing the incendiary potential of humor. All in the service of dislodging known, supposedly immutable, meanings, shifting them into an uncertain territory –exactly Hecate’s territory of the imprecise. Accompanied by Joyce, Davidson is choosing to wander in the imprecise space between classical mythology and modernist literature. Taking an extra step, she has tossed popular iconography and carnival spectacle into the mix. So, no, Davidson is not actually a necromancer, (not even close). Nonetheless she summons apparitions if not from the grave, then from banished margins of culture. In earlier work Davidson she has produced videos of roller derby and women’s rodeo. She has invoked the stilt walkers of Mardi-Gras and the carnival rituals that historically invert and travesty official culture. This is where she wanders, at the limits or the threshold of cultural illegitimacy.

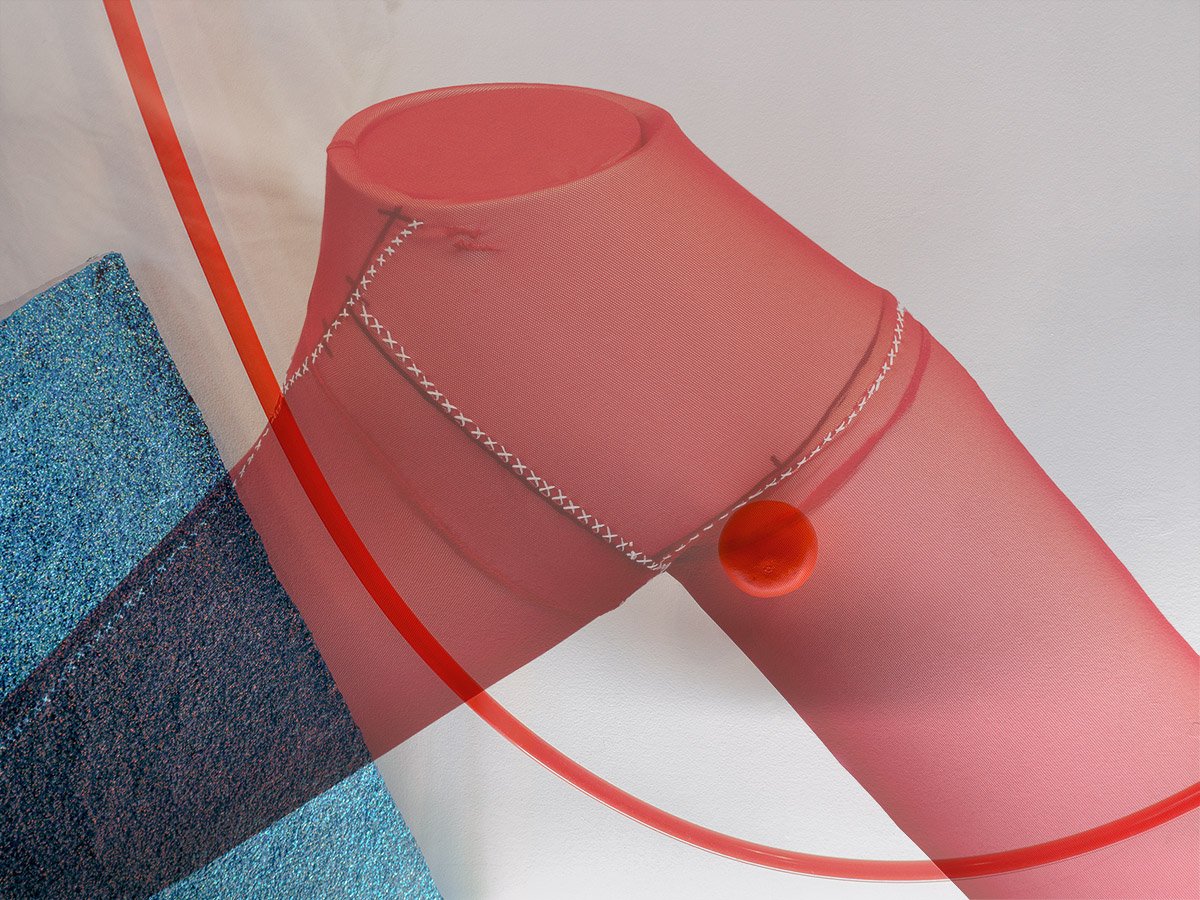

Probably the work Davidson is best known for are her balloons. Originally giant weather balloons posed as voluptuary beings, or parts thereof, they evoked breasts, buttocks, cleavage, bodily fears and fantasies. This is still a thread of Davidson’s work, though the balloons are now fabricated to her specifications. Davidson acknowledges that these sculptures are frequently associated with women’s bodies, the fetish lingerie, tassels and girdles lead one there. But she insists that they are also genderless. They could reference men, children, animals or even “hybrid bodies part human and part animal.”

And, if you were wondering, yes, there is a pinkly voluptuous balloon sculpture in the current show, Oyess, (2022). Oyess is sited in a large gallery facing across from the wall installation Source, which contains Hecatestick. Oyess itself is an eight-foot-tall agglomeration of inflated breasts, buttocks or balls. It grows in girth as it rises from floor toward ceiling. And behind Oyess, to its rear so to speak, is the floor to ceiling window of this former retail space. In this manner Oyess, somewhat brazenly, displays its voluptuary self to the world.

With Oyess Davidson is again in something of a conversation with Joyce. The title is borrowed from him, this time Finnegan’s Wake. These Joycean plays put language in a liminal place, put it in the process of becoming meaning. The words meaning is not immediate, not flagrant like the sculpture itself. One, negotiates with such words. One tippy toes around their relationship to the object they name. And one savors their imprecision because these words become objects in themselves. Finally, they enforce a regressive erotics of language, one is left as the infant struggling with its first words. This is language that destabilizes our way of understanding our world.

Overseeing pretty much all else in the show is Eyeenvy, (2017). At eleven feet tall Eyeenvy, a Cyclops, a one eyed giant, towers above all else in the show, viewers included. The piece is a science fiction riff spliced onto a prison guard-tower and a dilated pupil. Walter Benjamin once observed that ‘What we used to call art begins at a distance of two meters from the body. But now, in kitsch, the world of things advances on the human being”. Eyeenvy advances upon all it beholds, and it is certainly glitzy and plastic enough to embrace the name kitsch. So alongside carnival, alongside all other modes of popular culture that Davidson inverts and drags toward a liminal territory is she able to turn kitsch back upon itself? I am not sure she has to. It is more that she can appropriate its firepower. All the other work in the show speaks of the body in pieces. Nothing else in the show countenances the face. Eyeenvy stares you straight down but defies an empathic connection. Its kitschy visage resists and scares. Leaves one, perhaps, wandering and disconnected.

Benjamin, Walter; Dream Kitsch, Walter Benjamin Selected writings, volume 2, Belknap, 1999

About the author: Fintan Boyle is an artist, curator, and occasional contributor to the art blog Romanov Grave.

Green Legs, 2023, video clip, loop HD, 22” x 36”, edition of 3